Dissolving the Puzzle

Content Warning: this article discusses topics including self harm and suicide

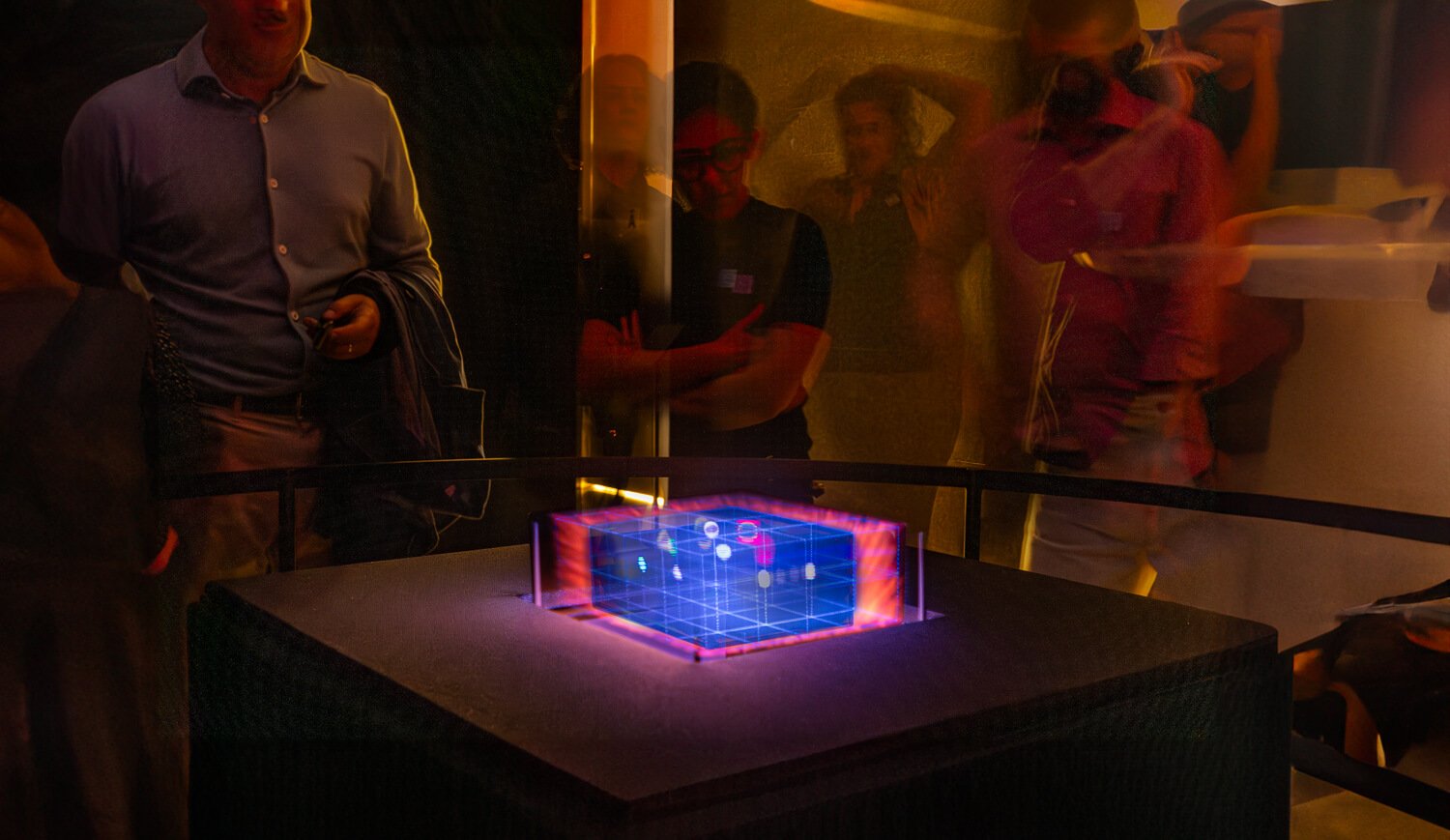

Image Credit: Museum of the Moving Image

Horror has covered a lot of ground in recent years, with content pushing boundaries by appearing in mediums like video games and youtube. David Levine's Dissolution, whose American debut at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, New York recently closed, pushes the envelope further by placing horror in a museum. Leveraging the novelty and abstraction of computers and artificial spaces, Levine weaves a story that's equal parts fascinating and unsettling, engrossing and disturbing. It’s also one of the most complicated pieces of art I’ve ever seen.

The exhibition, described by MoMI as “a jewel-box sculpture that conjures the past and future of the moving image,” consisted of a dark room, at the center of which sat a short black pedestal emitting a mechanical whir. Atop this pedestal was set a series of spinning glass panes, through which was shone a light such that they created a small three dimensional display, not more than a foot cubed and viewable from any angle. Speakers played the exhibition’s audio, and dark curtains kept the light of the room low. It's not quite a holoprojector from Star Wars, but if that's what you pictured you wouldn’t be far off.

The experience of watching the exhibit feels both new and familiar – the normalcy of video projection periodically intersected with the remembrance that what you’re watching isn’t a flat screen, but a full 3D form that you can physically walk around to see from different angles. The contents of the video short itself, however, are something different. Playing on loop is a twenty minute short film narrating the follies of modern society, told with visuals of video games and ancient art and narrated by the twisted and unsettling ramblings of the souls of humans trapped diegetically in the machine itself. For all the trappings of a “normal” exhibition it may have (overt critique of modern beauty standards, wealth disparities, and even the institutions of museums themselves stand out), I can’t help but feel its classification belongs somewhere else: the piece is, without a doubt, indie horror.

The short film itself isn’t so much scary as it is unsettling. Right from the start the audience is treated to a descent into madness as a basic demonstration of the display's ability to move colored lights around systematically morphs into an obsession with drowning. What starts as a basic demonstration of the technology, in which different colored lights appear and then and change shape and location to go along with the narrator's descriptions of the museum goers they are supposed to abstractly represent, slowly becomes an ode to drowning, as water fills the displayed museum and portions of Ariel's Song cut into the dialogue. By the time the “museum goers” are carted off on the back of a turtle, leaving only the wavering blue of unfathomable depths behind, the unease of the scene is palpable, the start of a deeply unsettled feeling that Dissolution manages to maintain throughout its entire twenty minute runtime.

Perhaps the most immediately striking part of Dissolution is its imagery. Covering everything from mansion hallways to cluttered beaches, the visuals are somehow both wildly varied and fully cohesive, tied together by the sense of the uncanny as, one after another, the scenes are revealed to be secretly dark and twisted. This is further cemented by the occasional breaks, places where a deep evil breaks through, showing itself for brief moments before retreating back into the subtexts. From the sharp toothed smile of a digital monster to the jerky movements of a disembodied eye, these moments of overt horror serve as tent poles, anchoring the short and providing a welcome release of tension from all the smaller hints that build up along the way.

Perhaps even better than its use of visuals, Dissolution masterfully uses audio to its full effect. The exhibit relies on several speakers, positioned at multiple points throughout the room. This allows it to play around not just with the sound itself, but with its layering, using the distortion of noise on top of noise to convey the preternatural nature of the piece. Coupled with a well written script and the result is a truly upsetting soundscape that could easily stand on its own. Even by my fourth viewing, I couldn’t help but jump at the various uses of audio. They, more than anything else, really sell the idea that something must be wrong. Because something is wrong.

This brings me to my favorite part of the entire piece: the story. Despite appearing at first to be driven by random aesthetic choices, rather than a more deeply laid narrative, Dissolution actually seems to have a much more cohesive story to tell than it lets on. As is common in this current generation of Indie Horror, the work relies on an approach of don’t show or tell, but rather leave countless little clues in the small details that only tell the complete story when cross referenced with the real world material being alluded to. As a result, watching Dissolution becomes a much more active experience, one that follows you out of the museum as you piece together what you think may have happened.

To that end, I think it's worth exploring this in a bit more detail. I’ve included below my own personal thoughts on the exhibit’s narrative, as well as the way in which I came to these conclusions:

“The best place to start is with the art exhibition itself. Namely, the fact that it exists in its own canon. There’s a point in the show where we’re shown several lines of pseudo code. All of them read, in some form or another, “if (real), then (do X),” where X is some form of saying or doing the action presented on screen (or I suppose “on glass”). Since this code always aligns with what’s actively happening, this tells us that what’s happening must be real. Later on we see a woman walking through an unknown space, surrounded by floating distorted texts. And there again, featured prominently amongst the floating text, is the word “real” repeated again and again. They even get so explicit as to describe themselves as being made of glass panes and as being a piece of art, describing exactly the setup of the show.

This brings us to the question of the main character. Levine’s website tells us that “Dissolution features a narrator who seems to have been forcibly removed from a glamorous, hedonistic life and trapped—as pure dematerialized consciousness—inside a strange and somewhat sinister digital realm.” This tells us that whoever we’re following isn’t just some rogue AI, it was once human. It also tells us that the protagonist’s name is Vox. This isn’t as useful as you might think, however, since Vox isn’t alone in the digital space. MoMI’s website tells us that the exhibit follows “human characters who find themselves dematerialized and confined within the interior worlds of electronic devices” (emphasis mine). This aligns with the way that Vox talks to herself: she’s constantly correcting herself, telling herself what to say and think, and changing her voice from line to line. She even goes so far as to explicitly refer to herself as a “we,” proving that there are, in fact, multiple people in the simulation.

This then begs the next logical question: if there are multiple pieces trapped in the exhibit, how and why did they end up there? This question seems to have two answers -- one for each batch of people. The first batch seems to have been forced into the transition. We meet Museos, whose name's spelling I've had to guess, a character we're told has been kidnapped in the basement of a museum and had their "body condemned to debt leveraged expansion." We're also told that Museos will "never see the real America," implying they're either a tourist or a recent immigrant, both groups that would be more susceptible to kidnappings.

It seems like the narrative of Dissolution is one of forced experiments -- the tours we get through the digital world show us various examples of video games that are not just competitive and violent but cyclical (a theme that appears a lot in Levine's work). To me, this implies that the people forced to become an AI are being trained in some way, much the way we train AI models in the real world. Given the violence of the games in question, the connection between the program and the weapons cache in the mansion the audience is shown, and the fact that we're told one of the museum goers in the opening scene has hair from the 70s (i.e. during the cold war), it seems likely that this program was a weapons experiment.

The project seems to have fallen through, however, as one of the voices makes reference to having been kept on a rich person's shelf for extended periods of time. It seems to have been dug up sometime in the 2010s, however, as we're told that the program was used to mine crypto. This seems to suggest that it was rediscovered and repurposed, perhaps without the knowledge of how it was made, and repurposed to fit whatever needs the family who controlled it had. Since we know that the experiment’s creators had access to museums, the reference to Museos being turned into an "earthwork and cultural center," seem to suggest that they 1) own museums, and 2) are using the AI to power miscellaneous projects they already have running.

This brings us to Vox herself. We can be fairly sure that she wasn't forced into the program -- we know she was rich from the official descriptions of the piece, which would make it unlikely that she was kidnapped and experimented on. We also know that Vox struggled with her mental health -- she describes directly how difficult she found her life and how miserable it made her. We're told that she struggled with wanting to be beautiful, and that she "wanted to press their face against the glass from the other side." It seems like she turned to the AI as a kind of escape, a way of leaving her own life behind to become a work of art.

There's one more significant question about the story of Dissolution -- the identity of the monster that occasionally appears throughout the story. As far as I can tell, this monster is Vox's father, who ran the experiments himself when they first began, only to willingly convert himself into an AI with the idea of ruling the real world from the computer. As far as his identity goes, one of the few things we're told explicitly is that the monster has teeth -- something that we're told was stolen from the people who were experimented on. This implied that the monster was the one who ran the experiments. We're also told repeatedly that art is an escape for the rich. If her father used the AI as an escape, that would be literally true. Finally, early on we're played a clip of Ariel's song, a song that in Shakespeare's Tempest is sung to someone who thinks, wrongly, that their father has drowned, only to later learn the truth. There's also a quote from Blade Runner's Roy Batty included, implying that the machine has some form of desire to revolt against the organic world.”

The story of Dissolution is the story of a family at the top of society. It tells the story of one man's abuse of power, kidnapping and experimenting on the disenfranchised for his own personal gain. It tells the story of his eventual rediscovery of his own experiment and his retreat into technology in an attempt to escape the world he helped create. And, once his daughter finds the technology, it tells the story of her eventual entrapment within it as that same world pushes her to suicide.

Ultimately, this reading is incomplete. Dissolution covers so much ground, presenting the viewer with so much information that it would be infeasible to cover all of it. I’ve attempted to pull every thread I saw, but with this much present in a live experience, some stuff will always slip through. That’s a part of the beauty of this sort of experience – no matter how hard you think about it, there will always be something else to decipher.

The exhibition wasn’t perfect. The horror and unease it creates, while definitely present, are relatively soft in the current day and age. While it captures the zeitgeist of double narrative indie horror, the success of franchises like Five Nights at Freddie’s, Poppy’s Playtime, The Walton Files, and Kane Parson’s Backrooms has pushed the boundary on acceptable content to the point where many of the themes and implications Dissolution offers lack the shock value it seems to expect them to command. Still, this is the first I’ve heard of bringing this genre to the realm of museum exhibitions, and for that it deserves some lenience.

All told, Dissolution is a wonderful installment. It pushes boundaries of what mediums you can use to tell an in-depth story, and it does so with a level of detail and care that I worry I can’t capture in portraying second hand. When I finally left, after the credits rolled for the fourth time, I didn’t leave because I was done. I left because I had blown past my allotted hour and had to get home. It was worth every second – I’m genuinely excited to see what Levine does next.