Still Can’t Help Myself

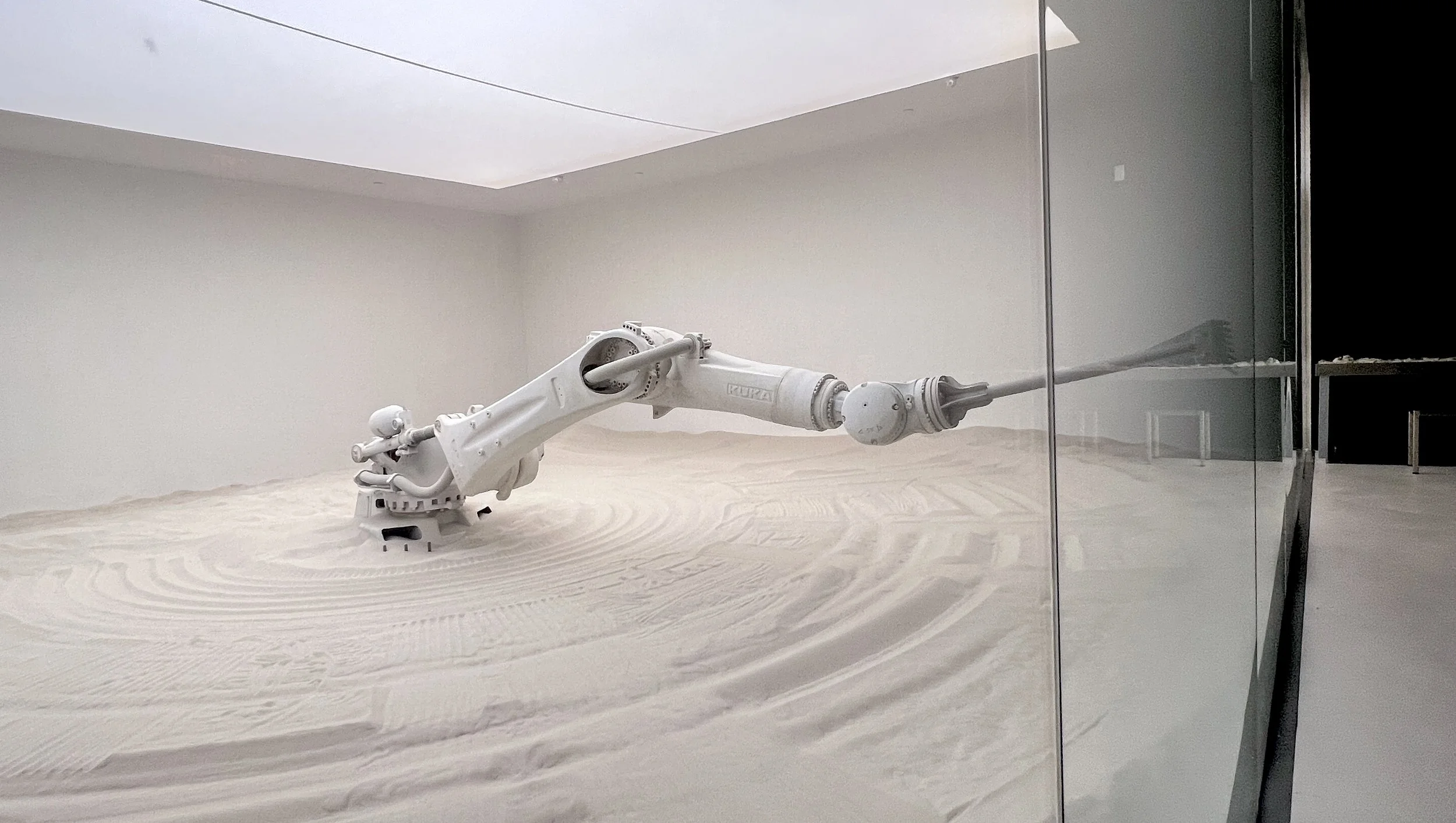

The Beach is easily the main event at Israeli contemporary artist Roy Nachum’s Mercer Labs exhibition. It’s a ray of bright light after an hour of trekking through linear darkness and overstimulated vibrancy. The white robot arm stands in the center of the white room. Pale beige sand on the floor surrounds the machine completely. Behind the accent wall of glass, onlookers watch as the robot rakes its arm through the sand, alternating between the action of creating and the action of destroying. In the sand, the robot signs Nachum’s name, draws Nachum’s signature crowns, and writes messages such as “I AM FREEDOM,” “i wish for a friend,” and “LOVE OU.” Some of the words are often cut off due to the sand being uneven. When the robot destroys, it makes thoughtless quick large arcs across the sand from one side to the other, almost as if it was programmed to do so. When the robot destroys, it makes small strokes towards itself, moving slowly, mechanically.

I sat there looking at The Beach for an hour. People came and went. I sat there wanting to feel a sense of astonishment, empathy, or some kind of epiphany. Though alas, nothing came. So I stood up and walked out, finding myself suddenly in the Mercer Labs gift shop. (Although it wasn’t the first opportunity that I had to make a purchase that day. Another shop where you can purchase flavored water and big lollipops is built into the exhibition itself inside a flowery pink cave. And not to mention the $50 admission price that I had paid). Before I knew it, the experience was over.

Let’s be frank: The Beach was, at the least, heavily inspired by Chinese conceptual artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s 2016 Guggenheim commission, Can’t Help Myself. Despite going formally out of commission by 2019, Can’t Help Myself rose to popularity in late 2021 after videos, pictures, and analyses of the work went viral across various social media sites like TikTok, Twitter, Tumblr, and Facebook. The work, often colloquially known as “the blood robot,” featured a robot arm in the center of a clear room as it attempted to contain a thick red pool of liquid that surrounded it. The arm twisted around itself as it frantically scrapped the fluid liquid back into itself as close as it could. Over time, it began to move slower, becoming weaker as red smudges and splashes stained its floors and windows – its purpose, a never-ending task.

When compared to Can’t Help Myself, The Beach falters completely. In its artistic statement, The Beach is described as a robot that takes on Nachum’s “alter-ego” as it conceptually moves through “different human emotions in the presence of natural elements.” The statement continues, “moments of innocence versus moments of intense emotion, connect viewer to nature and explore the implications nature and technology have on our mental state.” The beauty of art has always been that your experience of a work is subjective and entirely your own. It was part of why Can’t Help Myself garnered so much love and attention online. Many interpretations of the work, found in comment sections and online forums, deviate entirely from Sun and Peng’s original intentions behind the work. What started as a commentary on surveillance, voyeurism, and the human-machine relationship evolved into a work that explored exploitation under capitalism, a metaphor for addiction or self-harm, or human violence and its connections to technology. So let’s consider The Beach for a second. While it may have failed to inspire any visceral feelings, in some ways, it was kind of meditative. With the robot arm systematically raking through the sand, it’s almost reminiscent of the zen garden — miniature stylized landscapes of rocks, moss, wood, and prominently, gravel or sand used by Japanese Buddhist temples to imitate the essence of nature. I suppose an imitation is all it is. As an imitation, the message behind The Beach felt vague and shallow. Its artistic statement was a good suggestion. I wish I had felt connected to the sand robot. I wonder why I couldn’t.

When Nachum co-opted Sun and Peng’s idea and personalized it as if it were his own, he changed the robot into a superficial spectacle that conveyed nothing of note. And The Beach isn’t the only piece of work at Mercer Labs that shares eerie similarities with existing installations. The Dragon Room is comparable to Japanese contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama’s famous Infinity Mirror Rooms while Ecosystem employs the same concept and technology as the Japan-based, international art collective teamLab’s Sketch Aquarium. Despite this, there are no acknowledgments of Sun and Peng, of Kusama, or of teamLab anywhere to be found at Nachum’s Mercer Labs exhibition. On the Mercer Labs Instagram, under posts of The Beach, the team deletes mentions of Sun and Peng’s accounts and comments that refer to Can’t Help Myself. What are they afraid of?

In an era where plagiarism and art theft are becoming easier than ever through the use of new generative AI technologies, artists must begin to reevaluate themselves. How do artists now exist, perhaps as a community, when there is another entity also making art? What do we owe to each other and what do we owe to ourselves? This must be on Nachum’s mind as well, with The Beach also described as “a conduit for the artistic process while demonstrating the evolving relationship between humans and automation.” What is the artistic process if not a constant cycle of conversation and inspiration? Alone as artists and together with the community that you’re a part of — the line between inspiration and plagiarism is something drawn by ourselves. By refusing to address the original pieces that are undeniably connected to his own, Nachum must’ve found himself on the wrong side of it.